Little Places

Illustrations by Shiree Sutton

Originally published in Ghosts, Spirits and Specters: Volume 1 by HellBound Books Publishing

I never much cared for little places, where you can't stretch out both your arms and legs till your muscles creak and your whole body shakes just a bit. I make do buying a house with an "open" layout. Closets are walk-ins and when even that seems too small, I ask my wife. When something breaks, I hire a professional to crawl under the house.

It isn't a big deal. I drive a hatchback with enough room to lie down in the back. The only thing claustrophobia really ruined for me was Harry Potter. I didn't make it past where the boy lives in a little room under the stairs.

I dream of little places sometimes. It's dark, but warm -- too warm really -- and when I kick, my leg hits something with a hollow woody sound. It's just inches above me. I try to push the object off of me, but whatever is holding my feet isn't laid across my chest. Instead my arms reach straight up into the darkness. So I wriggle, trying to pull my whole body into the gap, but I can't move my legs.

In the real world, my phone is ringing. It's late, and my wife doesn't respond to the angry chirp of my phone. The screen tells me it is 2 am, and answering the phone is just a foggy reflex without conscious thought behind it.

It's my mom.

"He's gotten worse," she says, but her voice isn't sad. It isn't anything except maybe tired.

"Do I need to come?"

"Yes," she says. "I'm not going to, but he's your father."

She washed her hands of him long ago, but next of kin is next of kin.

I wake my wife.

"My dad is dying," I say.

She nods silently and rolls over. I'll ask in the morning if she processed what I said.

I'm up for now, so I grab a beer and collapse in my chair out in the darkness of the living room. I email my boss from my phone and buy a couple of plane tickets.

It's a seven hour trip: four in the air, one in Minneapolis, another in the air, then it's an hour from the little airport down into the valley. My father dies when we're somewhere over Iowa. I'm relieved that I've been spared having to see him, but I still have to finish the trip. I have a funeral to plan, a grave site to buy, and my father's house. In the end, the funeral is small and we opt to cremate my father. The house is unfit for sale.

It's an ugly 70s sprawl with a large first floor and a second floor loft tacked on as an afterthought. The hallways are narrow and the living room sits a couple of steps lower than the dining area and kitchen it's tied to. The walls are wood paneling, but the thin kind that splinters. The floorplan leaves hallways dark and far from windows.

"It's charming," my wife says as I pull into the driveway.

I put the car in park and turn off the engine. "Not how I'd describe it," I say.

"It needs a new coat of paint and some things," she says.

"It needs bulldozed."

"Hush," she laughs.

I don't feel like laughing, but I do anyway.

The house is bigger than I remember, opening up from it's double wide green door with a knob right in the center.

The door opens straight into a wall. To the right is a small sitting room and to the left is the kitchen and bedrooms.

My wife comments on the family crest displayed proudly on the wall.

"Yeah," I say. "My dad liked to go on and on about just how Irish we really are. As if the O' in the name didn't give it away."

"Should we take it with us?" she asks.

"What? No."

"Just a thought," she says. "This place is pretty nice."

"It's alright."

"No, I just mean that I thought you were poor," she says, running her fingers around a framed mountain painting on the wall.

"We were, sort of, I mean. My dad worked in the mines most of my life. Got a job with the union later on and eventually became union treasurer. We did alright."

"I see. Where is your room?" she asks with a smile.

"I'm sure it's just storage now."

But it wasn't. The room was just empty save for the bare mattress I slept on as a child.

"It's rather spartan," she says. She is still laughing easily; she knows that her laugh calms my nerves.

"Well all my stuff is gone, obviously," I say, but I'm scared to tell her the truth. The room had always been bare. I had made an effort to plaster the walls with band posters and sports stars, but when I was grounded my dad ripped those things off the wall. I was grounded a lot, so I stopped trying.

"So this is where you first discovered masturbation," she says.

"I suppose so," but I didn't laugh. I really should have laughed. "But I remember it for other things."

"Like what? First joint?"

"Can you imagine?" I ask. "If I were that stupid? My dad would have killed me, and my mom, well she would have let it happen." I pause to look at the bare bed. "Let me show you the rest of the house."

She flops down on my old bed. "Ew," she says, jumping back up. "Smells like pee."

"Dad kept a lot of cats after I left."

"Sure, cats," she chides.

She is trying to lighten the mood, but the comment upsets me.

"I didn't spend much time here," I say. "If you really want to know what it was like growing up we need to see the school and the library and the park and -- most importantly -- the woods!"

"Lead on," she says.

I took her out the kitchen door into the patchy grass behind the house. From this side, the house appeared much older. The siding had never been replaced. The trim had never been repainted. The bare dirt between patches of thick crabgrass made this look like the yard of a trailer. All it needed to complete the picture was a line of old vehicles on blocks.

"My dad was never persnickety about the lawn, well except when I was between the ages of 8 and 18."

She laughs. "A good lawn is a character builder. That's what my dad said."

"You had brothers."

"Right, and they needed to build their character more than I did," she smirks at me and I can't help but grab her hand.

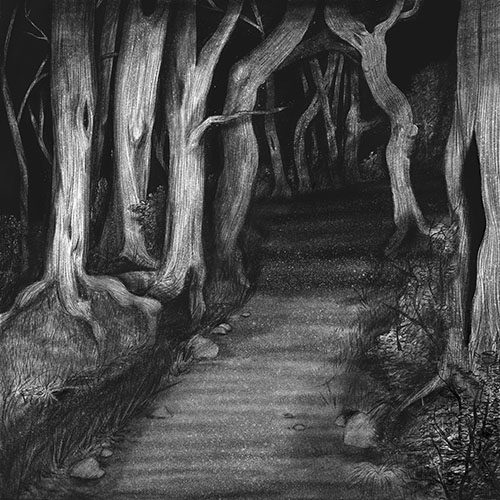

"Come on," I say. I take off dragging her behind me into the stands of elm, birch, and maple behind the house. "I used to play way back here," I say, jogging through the thick bed of leaves. "It goes on for miles!"

"How far are we going?" she asks.

"Up for a walk to the creek?"

"I don't have any idea how far that is, so yes?"

We walk far back into the trees, past the point where the sky grows dark as the trees close over it. The wind is whistling a trill note through the bare branches, a note I felt more in the hairs on the back of my neck than heard with my ears. It isn't accompanied by the chill of the autumn breeze, not down near the rot of fallen leaves.

"I don't remember it being this thick back here," I say stepping through the leaves and fallen twigs with heavy crunching footfalls.

"You were much smaller," she says. "Oh look, a rock-a-pile!"

"A rock-a-pile?"

She is pointing ahead to where someone had piled a little stack of rocks on top of a little mound of leaves and dirt.

"That's called a cairn," I say.

"No normal person knows that. It's a pile of rocks, a rock-a-pile, and it means kids still play back here."

"I guess so," I say, pressing on past the little marker, but I thought it a strange thing to find unless the precarious stones had somehow stood a long time. There weren't many houses in the area, and no proper neighborhood bordered the trees. When I was younger, there had been a few houses -- maybe three in total besides my own, but they were long abandoned by the time I hit high school.

"Perhaps one of the hospice workers had a kid that played back here," I say.

"Maybe," she shrugs.

The walk to the creek was impossibly long as a child, but as an adult it could be done in about 15 minutes. The creek is small and narrow, flowing swiftly as it babbled over exposed roots and stones. A kid of around 12 or 13 could have jumped it in a pinch. An adult could step right over.

"It was bigger when I was little," I say.

"Are you sure? I think perhaps you were just littler when you were little."

"Nah," I say, sitting down on a fallen tree. "It's still nice though, right?"

"It's a good picnic spot."

I put my arm around her and we sat in the woods just listening to the soft lapping of water. When we grew chilled and bored, we started our walk back to the house. The path we had tread in on was easy to see in the leaves, but thirty minutes passed us by without emerging into the backyard. I thought perhaps we had stayed too long at the little creek and that I had misread my watch when we left, but as day drew into twilight and our stomachs began to rumble it was clear we had been walking for too long.

"We must be going in circles," my wife says. She is exasperated, though this isn't the first time my directional skills had led us astray. Our light jackets are no longer enough to hold the cold at bay, and a chill has started to eat its way to my bones.

"I just followed the tracks," I say.

"Well it's not working. We must have looped back on ourselves."

"But we've never gone any way but uphill," I say, putting my arm around her. She goes to shrug me off, but she is nursing her own chill and presses against me instead.

"We haven't even passed that stupid rock-a-pile," she says.

The wind is crying, but I feel no breeze. The leaves don't rustle in the trees above us. I have never felt something so terribly wrong, and with my eyes closed I listen to the sound and strike out of our old trail in the opposite direction.

"What?" my wife says, noticing the sharp climb in our speed.

"You're right. We've been walking in circles," I say.

"Did you find the way?" she asks.

"Yes," I lie, but in a few minutes we pop out of the woods just a quarter mile down the road from my old house.

We don't speak of our time lost at dinner. We go to a little drive-thru place then back to the hotel to sit in silence. She is mad that I had gotten us lost. I am scared that I hadn't.

My wife and I explore my other old haunts, the high school, the library, the local parks. We don't hit any hiking trails and I don't suggest it, but in the end she runs out of time off, and I still have not started the odious task of cleaning out my father's home. With no other options, my wife buys herself a plane ticket and returns home while I set out to get as much done as quickly as possible. I don't want to be there much longer. I check out of our relatively nice hotel near downtown into a motel on the edges -- one of those motels with a number after the name that doubles as their rating out of 100. It is closer to my father's house, but more importantly it was $30 cheaper a night.

It is a cramped, dirty room. Just walking through the door set my nerves on edge, but it would do for a night's sleep.

I wake in the darkness of the motel room to the sound of the heater kicking on with a heavy clunk. I open my eyes but there is no light creeping through the curtains. I feel like I am floating in a sea of black, drowning in it. I roll to turn on the bedside lamp but find the blankets tied tightly around my feet.

The part of my brain normally buried by higher order functions turns on, and I thrash my legs, trying to move up the bed and away from the grip of my own covers.

The side of my face begins to hurt like it had been slammed against something, and without realizing it, I start to cry. I shout my wife's name into the dark, but in that instant the darkness recedes. It is gone. My feet came loose of the sheet like nothing had happened. The dim lights of the digital clock illuminate the bed.

I flick the light on and spend the early hours of the morning reading. I grab breakfast from the hotel lobby, store bought cookies and the cheap brand of yogurt, before heading back to my childhood home.

Daylight has chased away any real fear and now I just feel tired, numb.

It is still early morning when I arrive at my father's house with a couple of sandwiches from the local grocery store and a long to-do list. My father had died in the living room. He had spent the last few months of his life there on a rented hospital bed, next to a rented wheelchair, hooked up to a rented IV drip and a rented oxygen tank. The blankets would need laundered, the chair and bed disassembled and returned.

There is paperwork to be done, too. I'd need to find the deeds and titles to my father's house and car to take possession.

I did not expect it to be night when I finished, but as I close the house door behind me, I realize darkness has set in save for a single point of pale white light back in the trees. It is a small point and although I know there was nothing but more trees back in that direction, I tell myself it is merely a flood light on some distant house. I take a few steps off the porch towards the car and the light grows behind me.

I turn.

"Hello?" I say timidly, half expecting some hiker or local boy to come walking out of the woods. Another part of me, the same part I think that dreams of dark rooms, knows that the light is coming from some unnameable thing that stands entombed in those old woods.

A space as large as a truck is now filled with an iridescent glow, and I force myself to step towards it. One small step then another, straining my eyes into then light. It is like moonlight, soft and cold. My legs tense and my fists shut tightly.

I can make out a figure in the center. At first I think it to be tall and lanky, but while she -- and it certainly is a she, though I cannot say how I came to determine that -- has long arms hanging to her ankles, she is not tall. She is floating three or four feet from the ground and while I look at her I squeeze my keys so tight that the metal bites into the fatty underside of my fingers.

I take a single step backwards then, tripping over my own feet, turn and bolt towards my car.

But the figure in the light is faster. It shrieks like a cat in heat as it sails by me. I don't stay long enough to see where it stops. Instead I turn and sprint back into the house, slamming the door behind me.

I sink against the locked door and cover my face with my hands. I am too afraid to move even as far as the light switch, so I sit and rock myself, peering through my fingers into the shadows on the wall. I don't dare look through the window behind me at the unnatural light seeping through. I hug my knees and wait.

The family crest falls from the wall with a heavy bang and I leap from my resting place and dash to my old bedroom. The door was shut and although I shook the knob I can't push it open.

I find myself sitting against another wall between my door and the door to a second room whose purpose I can't recall. I must have fallen asleep in the hall because when I next open my eyes, the strange glow had been replaced with the first light of dawn. I stand and opened the door to the room beside my bedroom. Beyond the door is a mirror image of my own room -- a single bed, a single blanket in an otherwise spartan space. I feel strangely disoriented and move back to my room. It is still there, and so I am seeing things correctly. It opens easily now that day has come. The house has two bedrooms, mine and another.

It takes me a while to work up the courage to leave the house, but eventually I make my way to a coffee shop where I catch up on my work and current events. By mid-afternoon I had decided what to do with the house. It needed to be gutted and ripped apart, and for all the memories living there, I needed to be the one to do it. Once the memories were gone, I could hire a contractor to tear down the final beams. I'd sell the land and set aside the money.

I pack up my things and head to the local hardware store, a little family place that has stood in the town for some 50 years. The front door opens directly into a mixed help / checkout table so that the employees could greet you as soon as you entered. I remember coming here on my own as a teenager and dreading it every time. I always felt bad telling the employees that I knew where I was going and how to find what I was looking for.

It is an old man behind the desk today.

"Kin I help ya?" he asks.

"Yeah, I'm looking for," but he cuts me off.

"You're the O'Connell boy, aren't ya?"

"Yeah," I say.

"I'm sorry for bringin' it up. Ya look just like ‘im. Same brow. Same hair."

"Receding," I say.

The old man smiles at me. "Same humor."

I wouldn't have known. I don't recall my father joking around much, not when I was around at least. But he was well-liked by coworkers and his fellow unionists. I don't tell the old man this.

"I was sorry to ‘ear he ‘ad passed. Condolences," he says, but the word condolences rolled out of his mouth like it was a proud trinket he was showing off. A five dollar word in a sea of pennies.

I thank him, trying to hide my discomfort.

"If I'd've known you was coming I would have gotten ya a card with a bible verse."

"Thank you," I say. "I appreciate the sentiment."

The man smiles broadly. "How can I help ya today?"

"I need a sledgehammer," I say.

His demeanor changes instantly and I wonder if I mispronounced the word somehow -- as if perhaps I had so mangled the sentence as to have been offensive.

"You betta not be tearin' the old place down. Your dad, he loved that house. Put a lot work inna it."

"I'm not tearing it down.".

"Then lez get you that hammer. I ‘member your father coming her one night after I closed up. Must've been some twenty years ago to buy hammer, nails, an' paneling. ‘Member it cause he woke me up. Looked like he'd seen a ghost. Think he jus' buildin' a shed."

The memory floods back to me. Years ago my father had put up a little storage shed in the back yard to store his lawn supplies. It was a bit of a surreal memory. I left the house to go to school, and instead of being at work, he was in the yard hammering together a little wood frame. I was too afraid to say anything to him, but that wasn't unusual. I was often afraid of the man.

Somewhere in that recollection, I also remember him hauling wood into the house while I hid. I don't know if it was the same memory. It seems unlikely that wood for a shed would have ever been inside the house.

"That shed fell down if I recall correctly," I say.

The old man laughs.

"I think he was a better miner," I say with a smile, but there was something in the back of my mind clawing its way forward, and without thinking, I asked, "Did he buy anything else?"

"Oh I dunt ‘member that. Lye, p'haps. He wud always buying cleaners. Why you asking?"

"I just feel like I remember that night for some reason."

"Wudn't surprise me. It was odd."

I pay for the sledgehammer and head back to the house. I don't expect it to be growing dark when I arrive, but I barely take note of the falling twilight. Time has not made any sense since I arrived here. It's noon, then it's 3, then it's nearly 7, and the sun is starting to set without me seeing any of the time in between. I enter the house -- sledgehammer in hand -- in a disoriented fugue.

I swing first at the family crest that had fallen the night before. It bounces up off the hard floor, so I pour myself into the next blow, bending my knees as the hammer falls. The crest bursts apart. For good measure I put the sledgehammer through the wall where the crest had once hung.

It isn't the first time that wall had a hole punched in it. Being the first place my father saw when he entered the house, it was the frequent target of his indiscriminate rage. The paneling had been patched and replaced several times, but the sledgehammer didn't care that the wall was old and calloused.

I take the hammer into the kitchen and swing it from over my head into the corner of the kitchen sink where my father had held me upside down under the water. I was six, and he was upset that I had cursed. It is one of my earliest memories that I remember with any clarity. It takes several strokes before the cabinet shatters and the sink falls in, held up only by the heavy metal drain pipe.

I take the hammer into the hallway where my room sits and knock the knob out of the door so that it could never be locked in on me again. Finding that insufficient, I strike again and again until I have knocked the door from its hinges and the hinges from the frame. I flip the bed in the room against the wall. It is not as cathartic as the damage I had done to the door and kitchen, so I take my hammer to the wall of the master bedroom.

I smash a hole in the wall where I had cried listening to my mother and father fight on the other side. It is also where my father had knocked two of my teeth out. I was fourteen, and I had gotten between my fighting parents. I reduce the wall down to its studs, and when only the skeleton of the room remained, skinned by my hand, darkness has fallen completely.

Panting in the chilly, drafty air, I notice for the first time that my work was lit by the eerie glow from the trees -- filtering through the master bedroom's windows. Like that glow, something was seething from deep inside my mind, hammering its way out.

Unready to face it again, I run down the stairs, sledgehammer still in hand. When I reach the bottom of the stairs, I turn, gasping for breath, but the windows are dark again. I tell myself the moonlight was just cutting through the clouds -- that nothing unusual is happening. I am good at these kinds of lies. I'd been making them my whole life.

The front door creaks open and crashes loudly against the wall, but I don't dare turn around. The light was behind me now, illuminating the wall from just over my shoulder. I thought to run back upstairs, leap from a second floor window and dash to my rental car, but the light is there too now -- slowly advancing towards the stairs.

The only way left is through the wall under the stairs. The wall that was always rotting -- dry but moldy -- and my father would paint over it again and again and the black mold would appear again. It is rotten now. Black with mold like dried blood drops.

I scream as I swing my hammer into it.

The paneling splinters like matchsticks.

Behind the wall is an old door to a storage area, long ago nailed shut.

"No," I say. "Please."

But I don't know who I'm pleading with -- myself or the figure. I could feel her now, directly behind me, her light illuminating the door in front of me and casting my long shadow on it. I did not dare to turn around.

The figure's hand creeps over my shoulder and I scream, swinging my hammer into the door. The sledge catches the other side, and I tug with my whole body and all the energy left in my frame.

The nails pull from the spongy wall and the hinges give way, revealing the inside of a tiny storage room, and the shriveled body of my older sister.

The figure passes through me like a wave crashing across a rocky beach, and feels simultaneously cold as the grave and warm as sunlight. The force of it shoves me into the room so that I strike my head on the low bridge of the door and stumble helplessly over the body in a pantomime of my sister's death. The figure and its light are gone now, but the moon shone through the windows and down the hallway into the room.

We are face-to-face, my sister and me, and for just a moment she looks as she once did. Her bright blue eyes staring up at me one last time before they were gone again.

I was eleven when she died. I had hit puberty earlier than my friends, and my arms shot out, spindly, thin, and awkward. I spent my seventh grade year pretending I wasn't growing up, holding on to my childhood for the normalcy it gave me. Cassie was 13 and just the opposite. She was eager to grow up -- precocious, fiery -- a mountain of trouble.

Dad was always mad at her, and I never understood why. Perhaps because she grew up too fast or because she looked too much like her mother, whom he also hated. I don't recall the specifics of the fight, there were so many to misremember. As I grew older the fights became intertwined, confused with one another. I do remember he ordered her into timeout, and she didn't go.

My last memory of her is him grabbing her by the front of her shirt, seizing a handful of hair in the process and lifting her off the ground. He carried her roughly to the door under the staircase where we went for timeouts and threw her through the doorway. Her head cracked on the top of the door.

I don't know what I did the next day when she was gone and the room was walled off. I was afraid. So scared -- I forgot she ever existed. One little lie I told myself again and again till only the lie remained.

A week and a half after we buried my father, we bury my sister. The funeral is larger, with most of the town coming to offer their condolences and to tell me that they thought she had gone to camp, or had been taken by her biological mom or some other falsehood started by a small town rumor mill. My mother -- her mother -- didn't bother making the trip.

The local paper ran the headline, "House on Knoll Hill St Holds Dark Secret." But it hadn't. Not really. Everyone knew who my father was. They knew he had a temper. They knew he drank. They knew he had a daughter. They just didn't care. It wasn't their business. And how could I blame them? I too had forced myself to forget.

I never told my wife about my sister's specter, though I did tell it to a counselor -- framing it as a dream I once had. The house is still there, still empty, nearly reclaimed by the forest. The forest can have it.

All Rights Reserved